#85: A Matter of Respect

A daily roundup of interesting links about music, culture and marketing

CULTURE THING:

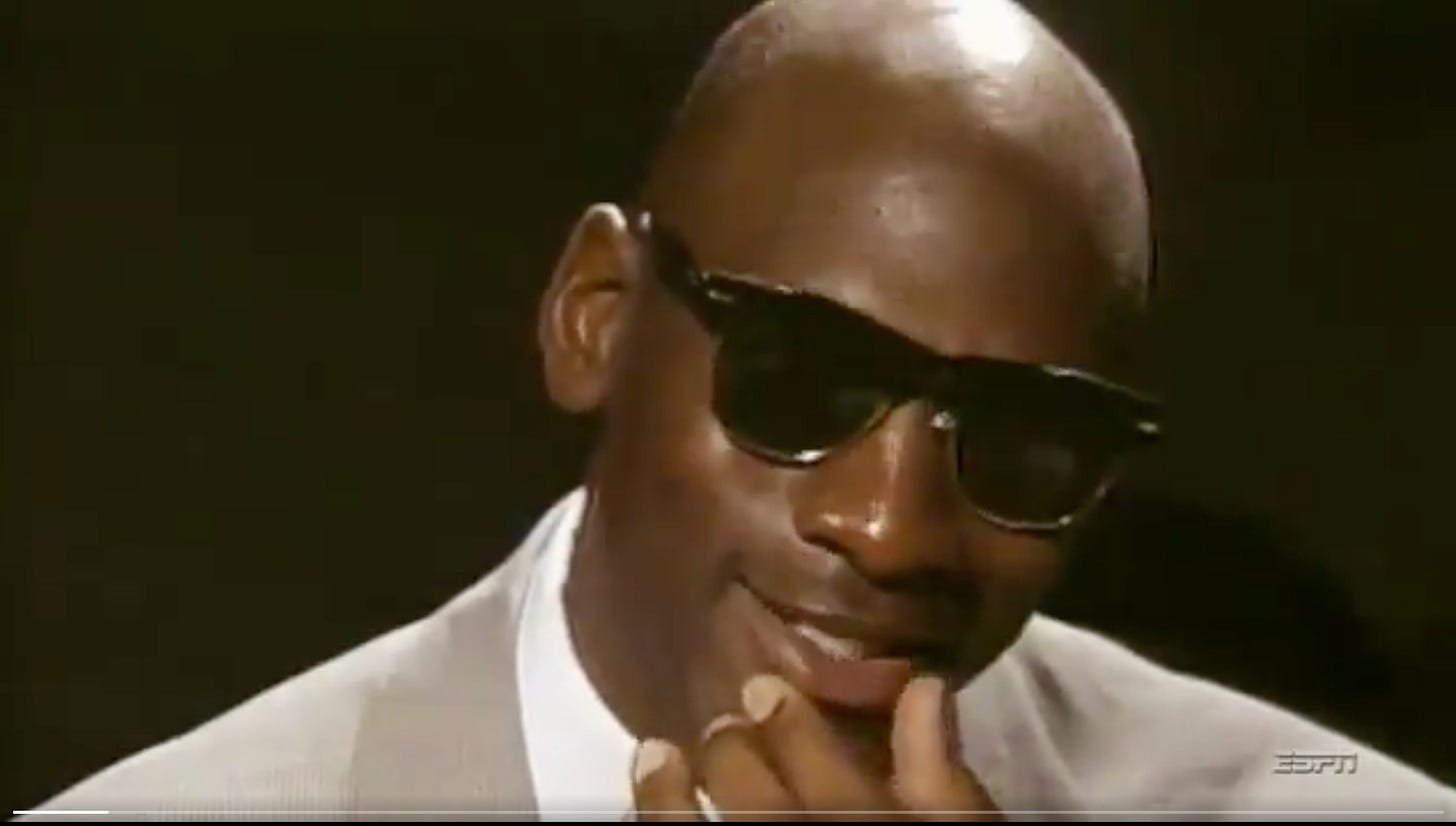

If you haven’t noticed by now, every Monday issue of Office Hours will be related to ESPN’s The Last Dance in some capacity for the remaining episodes of the series.

The Last Dance — the 10-part documentary about the 1990’s Chicago Bulls dynasty airing on ESPN — has seized attention and ratings to boot.

This week, I’m partnering with culture writer/sports historian Jack Silverstein to share an excerpt of his grail-level Q&A with Richard Esquinas that debuted over on his newsletter today.

I say “grail-level” sincerely, this is one of, if not the first time that Esquinas has spoken about his book since the early ‘90s.

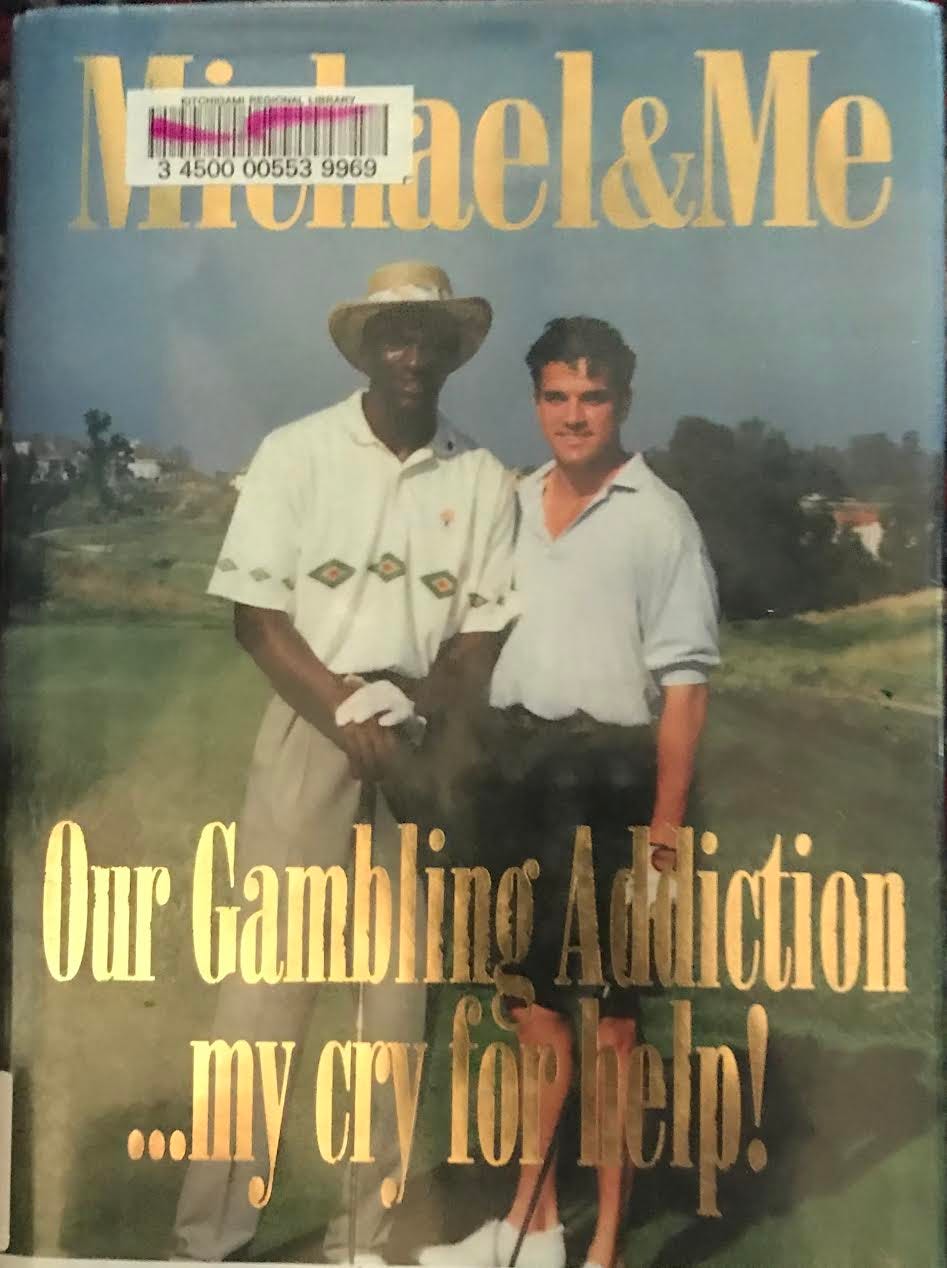

That book was a tell-all titled Michael & Me: Our Gambling Addiction … My Cry for Help! That’s the real title.

See?

Esquinas alleged that over a 10-day stretch of golf, Jordan lost $1.25 million to him. Later, Jordan negotiated to have the debt reduced to $300,000. Let’s get to it.

How To Support Office Hours

Office Hours can’t exist without support from readers like you. Here’s three easy ways you can support this newsletter:

Share this newsletter with a coworker/friend/loved one!

Become a paid supporter of the newsletter on an ongoing basis via this button:

Can’t commit to an ongoing subscription right now? Make a one-time donation as a way to show your support!

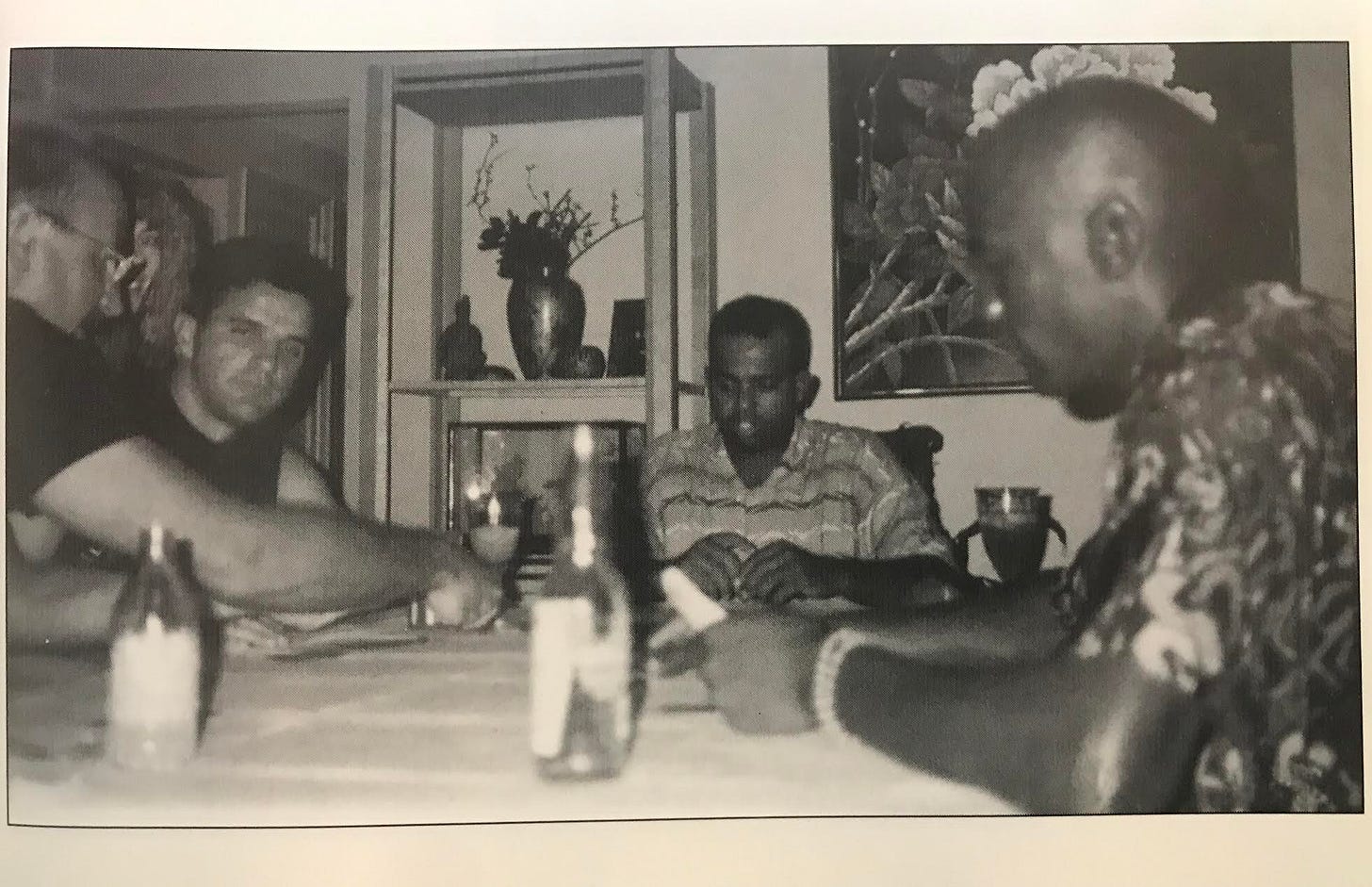

(Esquinas, second from left, facing camera, and Jordan, far right, playing cards.)

About the issue of getting Jordan to pay out his debt:

Were you taking handwritten or typed notes, or were you recording those calls with Jordan?

Both. And here’s why. That was the normal course of my business m.o. My phone was hardwired to a cassette player, because frequently I would be talking about contracts and deals, and I would want to go back to those recordings to get all the terms right, to go over the Ts and Is and make sure everything is tight in the contract.

That little skillset is a judicially-tested exercise for businessmen to prove things, that they have that normal procedure in their lives. So that wasn’t abnormal for me to take notes and/or record. That was the way I did business. That was normal for me. It wasn’t a scaled-up activity because I was dealing with Jordan.

Did Michael know that you were recording him?

I don’t know. He probably knew. Michael sat at my desk in my office and he saw the recorder attached to the phone. I used to use it for interviews. I never recorded all the conversations with Michael. But … I have recordings with Judge Lacey (from his meeting with Lacey in Manhattan on July 12, 1993), which he gave permission — we made the request and he gave me permission.

Do you have the notes or recordings from the calls with Jordan?

Yes. I put them all in one briefcase. That’s the core essence of that story. The last moments of me trying to get paid.

The central question is, MJ’s loaded, so why would he care about $1.2 million? You wrote in your book that it entered your mind that Jordan could not pay off his debt to you. Why did that enter your mind?

Well, I was in the heart of the sports and entertainment industry, and there are tons of examples — in the boxing world particularly — of guys making 25, 30 million dollars …and going through it. So I didn’t have such comfort to know that he was making 30 million a year and spending 40.

Was there anything that led you to believe at the time that it was possible that Jordan was living that make-30-spend-40 lifestyle?

No. There was such a platform of him talking about his balance sheet and us wagering and me getting paid “if I beat you, because I am coming to beat you, Michael. And if I win, I want to get paid.”

At this point, I was at least $600,000 (up) (Ed. note: $626,000) and I was looking for some low-level settlement, but if you’re going to rev it up and take it to this level then I want to get paid when I beat you.

So a million dollars in the scope of things, I was like, “He can handle that.” He had me convinced. So that’s where the conclusion comes. It’s not that he could not pay, it’s that he would not pay. I understand “can’t pay.” I’m empathetic. Guys can’t pay. I’ve had it happen to me.

But my point is, it wasn’t a “couldn’t pay.” It was “I won’t pay.” “I’m not gonna pay.” And that was the only thing where my spirit of forgiveness has trouble getting to. I can forgive a lot of things. … But the whole concept of “would not” vs. “could not” is the most perplexing. Do you understand that subtlety?

I do.

A guy comes to you and he’s pleading with you, “I can’t pay you, I can’t pay you,” then I say, “Take it easy, don’t get a divorce.”

But he never said that to you.

No. Michael said to the end, “I need a couple of months,” and I said, “Go ahead.” And remember, that’s already me coming off of my vow of wanting to get paid after the round. Because he should have come prepared to settle like I did when I gave him two ($98,000) checks.

Beyond this idea of him saying he needed a couple of weeks … did he ever say to you that he couldn’t pay?

No. Never. That would have been too humiliating for him. “I couldn’t pay” is not in his scope.

So what is your best guess? Why didn’t he just write you a check, or do the payment plan? What’s your guess?

I put a lot of time on that in my upcoming book, Michael & Me 2: Breaking Silence. But I think it contextualizes a lot of the things about him being the competitive predator that he is. I think the check was a concrete reality that he had lost big, and that somehow, by not giving it to me, it was somehow not quite admitting that he lost. That’s the deep, overarching sports predator analysis: What makes a guy like that go? They don’t like to lose.

He’s a competitor. He was squared in. The situation had been framed that, “I don’t want to play for this, but if we’re going to play for this, I’m going to go at it, and then we’re done.” It was that huge, very daunting game of golf, the high-stakes wagering, high-rollers thing, and he would not pay. And that is my innercore problem with this whole situation, to be quite candid: Why wouldn’t he pay me?

That is the ultimate question, because the reason you wrote the book was that he wouldn’t pay. And that book created way more problems for him than -

...than paying would have been.

For the full Q&A, as well as a detailed history of the book and a deeper look into why Jordan actually retired in 1993, go subscribe to Jack’s newsletter.

MARKETING THING:

A look back to 2003 and how Pabst Blue Ribbon became the stereotypical beer for the newly-rising “hipster” demographic. The Marketing of No Marketing

MUSIC THING:

How Nirvana almost broke up before their first album

Until tomorrow…

WASH YOUR HANDS! STAY IN THE HOUSE! CHECK ON YOUR LOVED ONES!

Office Hours is written by Ernest Wilkins. Follow me on Twitter/IG @ErnestWilkins or send me an e-mail.