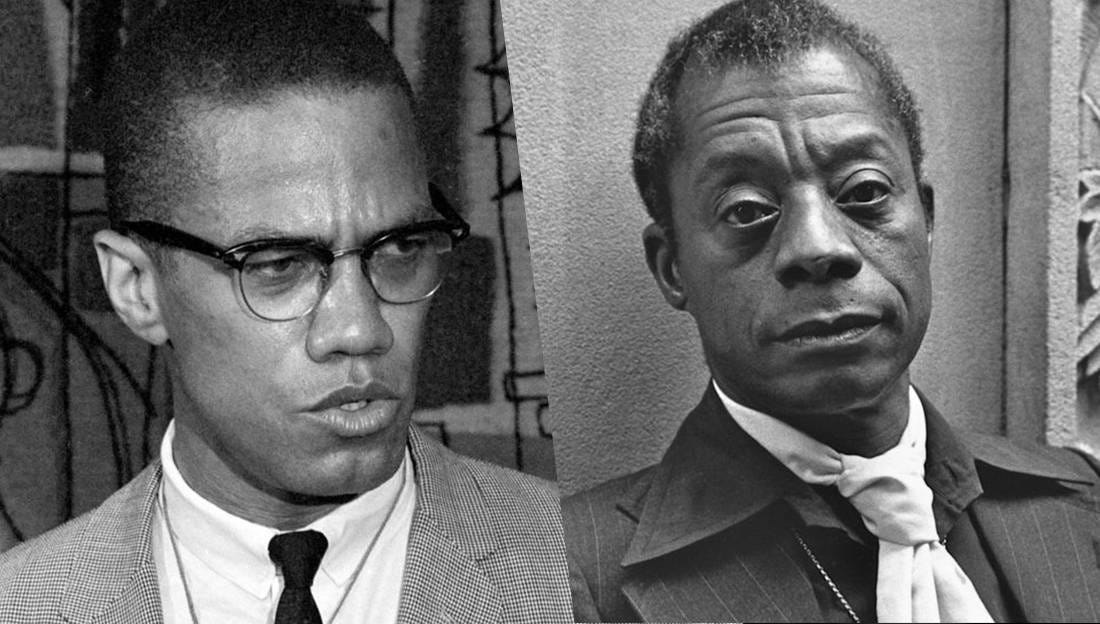

In 1963, James Baldwin had a lot going on. Earlier in the year, he released The Fire Next Time. For most of the year, he witnessed and participated in civil rights protests across the country, including the March on Washington. With so much going on, he had much to discuss with Malcolm X during a debate between the two, broadcasted on radio from Chicago on September 5th, 1963.

The two men were at odds. Baldwin advocated strong and purposeful action but never wavered his approach from using peaceful methods to achieve results. Malcolm X, by contrast, saw no path forward for Black America without aggressively claiming rights for not only Blacks, but all oppressed peoples. To Malcolm, any concessions made in the face of passive movements or “respectable protests” would be framed as gifts from the oppressors. Equality could not be given; it had to be taken.

Almost 60 years later, the discussion is both inspiring and depressing. While a great discussion between two of the smartest men to ever stand on American soil, the reality is that many of the issues that both men discuss still plague this country generations later.

The full transcript of the debate can be found below.

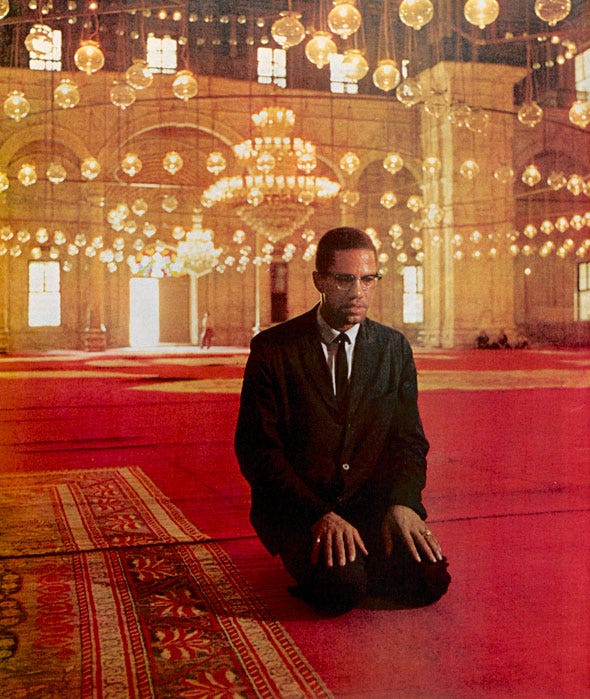

(Malcolm X prays in the great Mosque of Mohammed Ali in Cairo, where he began his movement among African leaders to indict America before the United Nations for racial crimes. From The Saturday Evening Post, September 1964, Photo by John Launois, © SEPS)

MALCOLM X: First, I would like to say that I am speaking, not for myself, but as a follower and helper and representative of the Honorable Elijah Muhammad, who is the spiritual head of the fastest-growing group, religious group, of black people here in the Western Hemisphere. And when we give our views, we don’t give them as a civic group. We don’t give them as a political group. But we give them primarily as a religious group. And any solution that we set forth, we absolutely feel that it’s a religious solution rather than a political solution.

One of the reasons that the Honorable Elijah Muhammad, in teaching us here in America, is giving us a solution that differs drastically from the sit-in movement, he’s trying to make us men. Now, the very fact that you find students all over the world today are standing up for their rights and fighting for their rights, but here in America the so-called Negro students have allowed themselves to be maneuvered under a tag of sit-in. Actually, I guess it describes — the name describes its nature. It’s a passive thing. And if their goal is integration, it’s not a worthwhile one. But if their goal is freedom, justice and equality, then that’s a worthwhile goal. If integration is going to give the black people in America complete freedom, complete justice and complete equality, then it’s a worthwhile goal. The holding this integration bottle and dangling it in front of the Negroes in America today has actually disabled them, or it has nullified their ability to stand up and fight like a man for something that is theirs by right, rather than to just sit around and beg and wait for the white man to make up his mind that they’re worthy to have this type thing.

I think that this is, in my opinion, why we disagree with the sit-in movement. If they are willing to wait for another hundred years for the white man to change his mind to accept them as a human being, then they’re wrong. But if they’re willing to lay down their life tonight, or in the morning, in order that we can have what is ours by right tonight, or in the morning, then it’s a good move. But as long as they’re willing to wait for the white man to make up his mind that they are qualified to be respected as human beings, then I’m afraid that all of their waiting and their planning is for naught.

As Thurgood Marshall said on New Year’s Eve, the Supreme Court brought about the desegregation decision, I think six or seven years ago, and there is only 6% desegregation in America right now. We don’t call two students, black students, going to University of Georgia integration, nor do we call four children, black children, going to school in New Orleans integration, nor do we call a handful of black students going to school in Little Rock integration. If every black man in the state of Arkansas can’t go to any school he want, that’s not integration. And if every black child in the state of Louisiana cannot go to any school that they are qualified for in the morning, then that’s not integration. And likewise with Georgia and any other state in America. It’s no integration with us, until the entire thing is given — is laid on the table, not a hundred years from now, but in the morning. And at the rate that the NAACP, CORE and the Urban League is willing to accept of attitude in the white man’s mind, we who are Muslims feel we’ll be sitting around here in America for another thousand years, not waiting for civil rights or something like that, but even waiting to be granted the rights of a human being.

(Writer James Baldwin at home in Saint Paul de Vence, South of France, in 1985. ULF ANDERSEN / GETTY IMAGES)

JAMES BALDWIN: I have the feeling that a great many words have been floating around, have been floating around this table, which need to be redefined. And that, by the way, is a problem, I think, which faces this entire country. I don’t agree with Mr. X about the sit-in movement. And I do know something about the war, incipient war, between the students and some of the leaders. I know the gap, the enormous gap, between the NAACP and the children in the South. I don’t agree that the sit-in—you know, I don’t agree that it is necessarily passive. I think it demands a tremendous amount of power, both in one’s personal life and in terms of political or polemical activity, sometimes to sit down and do nothing, or seem to do nothing. But finally, when the sit-in movement started, or when a great many things started in the Western world, it was not — I think it had a great deal less to do with equality than it had to do with power. And I do think we have to talk about — we have to decide what we want.

Now, what has happened in the world in relation to black people is not that white people have suddenly changed or become more conscious of the black man’s humanity. What has happened is very simple, which is that white power has been broken. And this means, among other things, that is no longer possible for an Englishman to describe an African and make the African believe it. It’s no longer possible for a white man in this country to tell a Negro who he is, and make the Negro believe this. The controlling image is absolutely gone. Now, it seems to me the responsibility which faces us then, the question which faces us, which faces me, in any case, is, since there is a distinction between power and equality, there is a distinction between power and freedom — and I know that in terms, for example, of Africa, that an African nation cannot expect to be respected unless it is free. I know that unless it has its political destiny in its own hands, which is what we mean by power, there is no hope that the English will deal with an African nation — they will deal with an African nation as a subjugated nation as long as it is in fact subjugated.

Now, this is not quite the same situation that we face here in America as American Negroes. I can see that I might very well, for one reason or another, leave this country tomorrow and never come back. But this will not make me — this will not cease — I will not cease to be an American Negro for this reason. And the history of — our history in this country is something that I think we have to face, especially since we’re demanding that white people face it. And whether I like it or not, whether you like it or not, this issue about integration is a false issue because we have been integrated here ever since we got here. I am no longer a pure African. There are no pure Africans in this country. The history which has produced us is something which, in any case, we’re going to have to deal with one of these days. And I think it is a mistake to pretend these issues did not happen.

What we’re arguing about, I think — one of the things, in any case, I think I would be arguing about is the effect of this on the Negro world and the great divisions in it, so that it does in fact range from people who imagine they are white, you know, who never talk to Negroes, to people who imagine that if they can make a buck, they will somehow beat the system, to homeless and demoralized black boys and girls who have nowhere — who don’t know where to go. The issue, it seems to me, the reason that the sit-in movement is important, the reason this whole ferment is of such importance, is not that I want anybody’s cup of coffee or even to go particularly to anybody’s school; it is because the country cannot afford — the country cannot afford to have, as it has at this moment, millions of black boys and girls in various ghettos all over the country either perishing literally or perishing, I must say, finally, with the kind of demoralization and bitterness and hatred which can, after all, blow this country wide apart.

The importance, in my mind, of the Muslim movement, in conclusion, is that it is the first time, I think, in the history of this country that a Negro audience, a Negro laborer, a Negro schoolboy has heard his own condition described without anybody trying to flinch from it. It is very different from hearing a speech by Roy Wilkins in which, you know, when it’s told, in one way or another, that tomorrow will be better. And I think this has a tremendous effect. This is the reason I think the Muslim speaker has so much power over his audience.

It comes out of a failure in the republic. This country had lied about the Negro situation for 100 years. And now what has happened is that the lies are no longer viable, can no longer be accepted, even when they can be told. And the country has waited so long, and it does not know how to handle this, and it’s created a moral vacuum. There’s a moral vacuum in the Negro ghettos in the same way there’s a moral vacuum in the audience, which is filled with desperate people. And I don’t think that we can afford this.

It seems to me — and now I speak for myself — my quarrel with the official Negro leadership and my quarrel with those such Negroes that imagine they are integrated or imagine they somehow escaped the Negro condition, is that they are not willing to do what I think is absolutely essential, and has got to reexamine the basis, the standards of this country, which do not only afflict black people. They afflict the entire country. No one in this country, as far as I can see, really knows any longer what it means to be an American. He does not know what he means by freedom. He does not know what he means by equality. We live in the most abysmal ignorance of not only the condition of 20 million Negroes in our midst, but of the whole nature of the life being lived in the rest of the world. And I think that the American white man, the republic, is paying, is beginning to pay for its treatment of the Negro in terms of what he doesn’t know about the rest of the world.

You cannot live, it seems to me, in — you cannot live 30 years, let’s say, with something in your closet, which you know is there, and pretend it is not there, without something terrible happening to you. By and by, what I cannot say — if I know that any one of you, you know, has murdered your brother, your mother, and the corpse is in this room and under the table, and I know it and you know it, and you know I know it, and we cannot talk about it, it takes no time at all before we cannot talk about anything, before absolute silence descends. And that kind of silence has descended on this country. I think that this country has become almost inconceivably radical overnight. It has really got to do something it has not done before, and this involves the humanity of everybody in it. And the key to this is in the Negro. If one can face that, one can face anything. But that has not been faced. And I think this is the reason for the confusion and the ferment and the great, great danger.

Again, let me say this, and I will stop. I am not religious. And therefore, since I am not religious, all theologies, for me, are suspect. All theologies have a certain use. But I never, for example, believed in the myth of the virgin birth, and I never quite understood why it was necessary to propagate such a peculiar notion. Therefore, you know, as theologies go, it seems to me the Muslim theology is just as good as any. One cannot quarrel with it there. I can’t anyway. But I personally — I personally reject that theology as I reject all others, and I don’t think that we need it.

Now, this is a great — this is a gamble. This is a very reckless thing to say. And perhaps, you know, I’m — perhaps this is very mystical. I know the kind of world I would like to see. I would like to think of myself as not needing to be supported by a myth. I would like to think of myself as being able to face whatever it is I have to face as me, dealing with what I have and what that is, without having my identity dependent on something which, finally, has to be believed, which cannot be tested. This is why one is converted to a religion, you know. I think that there is something very dangerous in it.

What I would like to see, and maybe we will never live to see it, is a world in which these things are not necessary, in which I will not need to invent, in effect, a heritage and a history, but I can deal with the one I have, and will not need, in order to — in order to deal with the rest of the world, will not need to feel superior to them, but simply be a part of them. And it seems to me this may happen, rather than, obviously, a world in which there are no blacks, there are no whites, where it does not matter, because as long as it does matter, as long as it does matter, and it doesn’t matter who is wearing the shoe, the confusion will be great, and the bloodshed will be great.

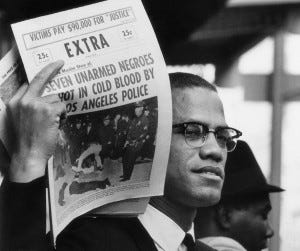

(Malcolm X Holding up Black Muslim Newspaper, Chicago, Illinois, 1963. Photo by Gordon Parks. Yes, THAT Gordon Parks.)

MALCOLM X: Well, I, as a black man, and proud of being a black man, I can’t conceive of myself as having any desire whatsoever to lose my identity. I wouldn’t want to live in a world where none of my kind existed. And I do think that the Negro, the American so-called Negro, is the only person on Earth who would be willing to lose his identity in what you might call a new product. I heard one fellow say one day that eventually intermarriage and intermixing would take place on such a vast scale that it would produce a chocolate-colored race. And Martin Luther King was in a discussion, televised discussion, with a white newspaperman. I saw it on the television a couple months ago. And this white newspaperman put this to him. He said — he pointed out that he’s proud of his white race. He’s proud of what he is. He’s proud of his racial characteristics, to the extent where he has no desire to lose it by mixing with any other race. And the thing that he said he couldn’t understand was why the so-called Negroes don’t have the same racial pride that whites have in trying to retain their characteristics. And Martin Luther King never answered him, although he should have answered him. I think that it’s disastrous for the black people in America to reach the point where their racial pride disappears, and they don’t want — they don’t care whether their blood is mixed up with someone else’s.

I think that also one of the things that brings this about, as the Honorable Elijah Muhammad teaches us, the very fact that you have to refer to the black man in America as a “Negro” shows you that right there something is wrong. An African doesn’t accept this term “Negro.” And you find they teach us in the educational system of this country that “Negro” is a Spanish word that’s supposed to mean “black.” Yet, when you find the black people who live in Spanish-speaking countries of South and Central America, they don’t accept the word “Negro” to identify themselves. No one allows himself to be classified under the word “Negro” but the black man here in America who is a descendant of the slaves. And very seldom is it ever applied to anybody but the black man in here, here in America, who is the descendant of the slaves. When you ask a man his identity, he should use a word that connects him with a culture. If you ask him his nationality, it should connect him with a nation, like if I ask a man his nationality and he says, “German,” that connects him with Germany. Or if he says — even if he says, “German-American,” it still connects him with having originated — his family, his history, has originated in Germany. If he says he’s French-American, it connects him with France. But when you ask the black man in America and he tells you Negro, he doesn’t put any other — he doesn’t put any other country in front; he puts “American Negro,” or he’ll just say, “Negro.” This doesn’t identify him. And usually, when you find a man who calls himself a Negro, he can’t tell you what language that he spoke before he came to this country. It’s of no consequence, no interest. He believes that prior to coming here, he was a savage in the jungle, and therefore he had no language, and this justifies his lack of knowledge concerning that mother tongue today.

And the history, as Mr. Baldwin pointed out, of the white man here in America and the black man here in America points up the fact that the Negro, or the man here who calls himself a Negro, is just an ex-slave. If he is an ex-slave — I’d rather say he’s still a slave, but he’s wearing his slavemaster’s name, the name that was given to him during slavery. He’s speaking the language of the man who made him a slave, because he has no knowledge of his own tongue. He only knows the history, his own history, as taught to him by his former slavemaster, who purposely hid from him his own history to make him think that he was an inferior being before being brought here.

And Mr. Muhammad teaches us that until the black man here in America is connected or reestablished or given some knowledge of his existence prior to coming here to America, his own appraisal of himself will be so low that he’ll actually think that the white man is doing him a favor to let him be here in America, no matter what his status is. And he also — and this is one of the reasons today why he fights so hard, some of them, to sit down next to the white man. They actually think that the white man is the personification of perfection. And whenever they’re allowed to go live in his neighborhood or sit in his restaurant or mingle or socialize with him, that they have attained, that they have made progress. But when they go back and study the history of their own people and the accomplishments of their own people, the civilization and cultures, black civilizations and black cultures that existed in Africa, at a time when the whites in Europe were living a cave-like existence, then immediately their appraisal of themselves begins to go higher, and they don’t think that to beg somebody to mingle with them in this country is any kind of progress whatsoever.

And I would like to say one more thing, too, on that nonviolent thing, that the black man in America is the only one who is encouraged to be nonviolent, or the black man in Africa or the black man in Asia. Never do you find white people encouraging other whites to be nonviolent. Whites idolize fighters. They idolize the Hungarian freedom fighters who came to this country and right now can work on jobs that the sit-in students can’t get, can live in neighborhoods that the sit-in students can’t live in, and can go into public places that the student sit-ins can’t go, because they are fighters. Everyone loves a fighter. They respect a fighter. But at the same time that they admire these fighters, they encourage the so-called Negro in America to get his desires fulfilled with a sit-in stroke or a passive approach or a love-your-enemy approach or pray for those who despitefully use you. This is insane.

And we feel, as Muslims, until we see white people practicing this nonviolence — take Pearl Harbor. When the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, the American white man didn’t say, “Pray for the Japanese, and let them now bomb Manhattan or Staten Island.” No, they said, “Praise the lord, but pass the ammunition.” And if anybody comes along, like Mr. Muhammad, and begins to point out uncompromisingly, in blunt terms that don’t need interpret [inaudible] diplomatic language that can be misinterpreted, and he begins to point out these atrocities and crimes that have been committed against black people here in America today, the white man can never deny the fact that he’s guilty, but he’ll always say, “Well, forget the past, and let’s look forward.” But the only people who are told to forget the injustices that have been done to them are the black people.

But when it comes to whites, right today, you can turn on any radio, turn on any television, read any newspaper, and the Jews have magnified to the world the crimes that were committed against them 20 years ago or so by Eichmann, and they keep you sitting on the edge of your seat wanting to strangle Eichmann and strangle the Germans. This is a — it’s almost like a hate Germany campaign. But yet the Jews are never accused of teaching hate because they remind the world of the crimes that were committed against them.

But when the black man here in America begins to stand up and speak about the crimes that are committed against him throughout America every day, no let up, just different forms, immediately a black man who dwells on that is considered a racist, considered an extremist or considered someone who is advocating a doctrine that will bring about violence and bring about a deterioration in the so-called good relations that are supposed to be developing between black and white in this country. So, we just can’t go along with any of that.

And I think that this is the thing that the white people of America should realize, that Mr. Muhammad’s teaching — and it’s spreading, so you have to deal with it — Mr. Muhammad’s teaching doesn’t teach the black man to wait for the white man to change his mind. Mr. Muhammad’s teaching is changing the black man’s appraisal of himself and changing the black — and as soon as the black man undergoes a reappraisal of himself and realizes that he’s a man, too, he says to himself: Why should he wait for the Supreme Court to give him what a white man has when he’s born? Why should he wait for the Congress or the Senate or the president to tell him that he should have this, when if he’s a man the same as that man is a man, he doesn’t need any president, he doesn’t need any Congress, he doesn’t need any Supreme Court, he doesn’t need anybody but himself to bring about that which is his, if he is a man?

(Baldwin in Paris. Photo by Sophie Bassouls / Getty Images)

JAMES BALDWIN: I think we — I think, in the first place, there’s some disagreement between Mr. Malcolm X and myself as to what this heritage is. And I want to go back to that in a minute. There’s something else, at the moment, that bothers me, that I think there’s a great deal — there’s a lot of — there’s not much clarity in this question of violence, from my point of view, from where I sit, whether or not — no matter what Mr. X wants, no matter what I want. I believe, for example, that one of these days, maybe tomorrow, Birmingham, Alabama, will probably blow up. And if Birmingham blows up, it will not just stretch to Atlanta. It will stretch to Boston. There’s a kind of fuse. There’s a kind of — there’s an undercurrent. There’s something which unites all Negroes in this country, so that what happens in Birmingham can blow up Harlem. It has happened before. And unless we are extremely swift and miraculously swift, it will happen again.

I take it — I take violence — I’m trying to say this: I take it as given. I think it is coming in any case. What exercises my mind is: What happens then? In the first place, this country, in its position in the world now, this extremely precarious position in the world now, the situation of the Negro here is different from that of the Jews in Germany, let us say, you know, 20 or 30 years ago, in that if Birmingham should blow up, if there should really erupt in America this week a really — a real, real racial violence, it would have repercussions all over the world. I’m afraid we have to face this fact, that when the Jews were being slaughtered in Germany in the very beginning, no one seemed to care. Millions of Jews crossed the world, boatloads of them, and no country would let them in. But the American Negro has something working for him in this context, or the country has something working against it, which I don’t think he can afford.

But I want to get back to this question of identity, because it seems to me this is where the — this is really where all the questions are. Mr. Malcolm X disagrees with the word “Negro.” And I can see his point. I confess it doesn’t much interest me, but that may be my fault. What I am concerned about, though, is the actual history of Negroes in this country. I think one has got to face the fact that it has been one of the ugliest histories in the history of the West. But if one can face this fact, well, there’s another factor which I think one has got to face, which is also one of the most remarkable histories that we know. And I’m not talking about all the good things that white people did, you know, for the poor darkies and all that jazz. I’m talking about the effect of this experience on the people who underwent it, the masters and the slaves, what it did to them.

I would be a very different person if I were not the descendant of a slave. In fact, I am the descendant of a slave, and this is one of the things that I have to deal with, because it is true. And I don’t think that it has to be a badge of shame. Negroes are not the only slaves. We are not the only descendants of slaves. I can’t eliminate one-half of my ancestors. My grandmother was raped, let us say. This is a fact I have to face. This means that I am no longer a pure African and that my relationship to white people is not that of a Congolese to Belgium, and cannot be, no matter how hard I try to make it that. My relationship to white people is dictated by my mother’s relationship to them, my father’s, by the fact that my grandmother nursed children who grew up to lynch her children, that my father’s fathers were always under the heel of some benevolent white man. And a whole myth of this experience has come into being in the country, which is at its highest seen in Faulkner and at its lowest seen in Margaret Mitchell. Now, I don’t think that we can be liberated from this history until we are willing to deal with it. And this means that I have to deal with it, as well as any white man in the country has to deal with it. There is really too much and too little to say.

What is the issue here? Malcolm X wants us to act like men. And it seems to me, one of the things that I object to here, I don’t think that the fact that white people have done what they have done — Patrick Henry is not one of my heroes. I’m sorry. Most of the American heroes have never been in my hall of fame. I don’t see any reason for me, at this late date, to begin modeling myself on an image which I’ve always found, frankly, to be mediocre and not a standard to which I myself could repair. I don’t think that black men now should be — because white men have committed these crimes, that black men should then — should do the same thing.

I think that there is something absolutely insidious — even if I cannot make this absolutely clear, there’s something, to my mind, always terribly insidious in the whole question of race. The white man’s racial characteristics, of which the white man claims to be so proud, have reduced him in this country to some — to incredible levels. There is nobody in the world, I think, sadder than a white man in the Deep South who only has his skin and his blue eyes and his yellow hair and nothing else. I don’t think that I want to go through the world, and I will not encourage my nephew to begin to go through the world, only armed with the color of his skin.

The only thing that really arms anybody, when the chips are down, is how closely, how thoroughly, he can relate to himself and deal with the world, yes, as a man, you know, but I don’t think — I think, when I talk about standards, I say they’ve all got to be revised. This is one of the standards that has to be revised. I don’t think that a warrior is necessarily a man. And, in fact, it has proven that football players and all these people in teams and in armies are not men. It is very difficult to be a man. And what it involves, for me, anyway, is an ability to look at the world, to look at whatever it is, and to say what it is and to deal with it, to face it, even if it does mean laying down your life, as, in a way, it always does mean that.

Office Hours is written and curated by Ernest Wilkins.

Follow me on Twitter/Clubhouse/IG @ErnestWilkins.

Want to work with me? Send me an e-mail.